Forts and Protection against Diseases

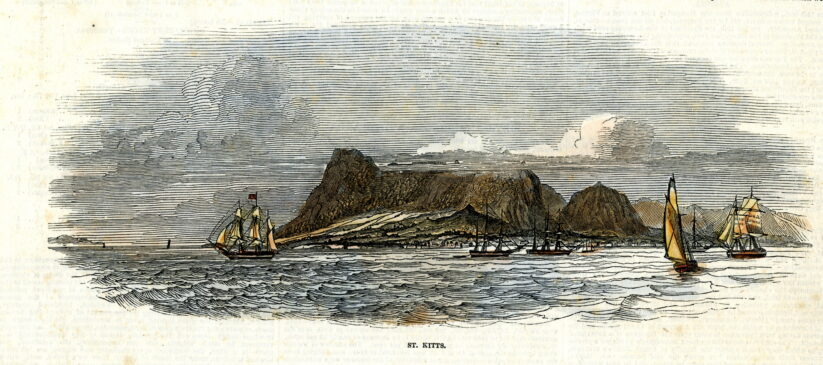

We are sharing today a print from 1848 that appeared in the Illustrated London News of that year. We went looking for it because Dr. Cameron Gill shared a piece with us about the drastic but necessary quarantine restrictions of the past. The unknowns in medicine and lack of personal hygiene made a lot of the measures that had to be taken far more stringent then what we are seeing today but the purpose was the same – to limit exposure.

The role of St. Kitts’ forts in past efforts to keep diseases away from our shores

Cameron Gill

Introduction

In their response to the Novel Coronavirus or Covid 19 pandemic several countries have included military assets as part of their response arsenal. For instance, Italy has deployed an Italian Air Force military transport aircraft to airlift vulnerable persons to care facilities. In New York City, one of the largest clusters of Covid 19 transmission in the United States, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has been placed on standby. Several countries have deployed their military to reinforce patrols along their borders as a means of attempting to halt the entry of infected persons. As with many other major events there are historic parallels. The following slightly amended excerpt from my Doctoral Dissertation highlights the role of coastal forts on St. Kitts during the 18th century in the official response to the bubonic plague and other infectious diseases such as syphilis.

St. Kitts coastal forts and 18th century plagues

The role of Sandy Point’s fortifications in preparation for possible attack is clearly illustrated in many official documents. For example, in 1678 rumours of an impending war between England and France prompted the Council and the Governor to reinforce Cleverley Hill Fort (Charles Fort), then the island’s chief fortification, by transferring artillery pieces to it from three other forts: Sandy Point Fort (Fort Hamilton), Stones Fort and Fort Charles in Old Road (CSP, A&W.I., 1677-1680, 215-220).

The response described above to fears of a possible French attack on St. Kitts typifies the traditional role of coastal forts, defending an important stretch of coastline from hostile enemies. Interestingly though, in the early eighteenth century the forts of St. Kitts were also tasked with defending the island from a completely different type of threat. Between 1722-1723 an Act was passed stipulating that vessels arriving at St. Kitts from parts of the world infected with the bubonic plague, smallpox and other infectious diseases be prevented from allowing its crew, passengers or cargo to land until it presented documents to satisfy authorities on the island that it had been properly quarantined. Responsibility fell upon the island’s coastal forts to enforce this legislation. A ship arriving off St. Kitts was to be hailed by the gunner of the fort guarding the port, anchorage or other stretch of coast that ship arrived at before the vessel was allowed to land goods or persons ashore. The ship was expected to respond by stating which country it had sailed from. If the ship came from an infected country (for example, the plague was prevalent in parts of France at the time) it would be refused permission to land cargo or persons. In the event of a ship arriving from an infected region trying to land anything or anyone in defiance of orders not to do so, the legislation instructed the gunner to open fire with small arms or artillery fire. Anyone who managed to land on shore from the vessel without the proper quarantine being performed was to be “put to Death with any Weapon (St. Kitts National Archives, Laws of the Island of St. Christopher; from the Year 1711 to the Year 1791).”

The provisions above applied to all of St. Kitts’ coastal forts. There was; however, a further provision which gave a specific role to Fig Tree Fort (or Fort Charles), the former French fortification sitting on the northern end of the Sandy Point Anchorage. Once a vessel had arrived from an infected country and been barred from landing goods or persons, the ship’s captain or master, if they did not wish to depart the waters of St. Kitts were allowed to anchor only off Fig Tree Fort at a distance of no less than one mile from shore. A ship carrying anyone infected with the plague may remain anchored at this spot for forty days, in the case of smallpox “or any contagious fever” for thirty days. After the respective stipulated period had passed a surgeon may board the vessel to conduct an inspection. The vessel would be permitted to land persons or goods only if the surgeon presented a certificate signed by himself to “any Magistrate in this Island” stating that there was no infected person aboard (ibid). As there would have been little, if any, effective treatment available aboard ship it is obvious that this offshore quarantine period, especially in the case of the bubonic plague, was intended to allow time for the victims to die out. The same provision stated that the surgeon, apart from ensuring that there were no infected persons aboard ship, was also to ensure that all bedding and clothing that had been used by infected persons had been burnt or otherwise destroyed (ibid).

So while all of St. Kitts’ coastal fortifications were tasked with keeping plagues at bay (in a literal sense), Fig Tree Fort on the northern bluff of Sandy Point Anchorage was given the additional role of, when necessary, enforcing a maritime quarantine of vessels arriving from countries afflicted with bubonic plague, smallpox or other highly infectious diseases. This contrasts sharply with the role the anchorage adopted at the ending of the following century. The anchorage became the official point of entry for sufferers of leprosy brought to St. Kitts to be housed and treated at Charles Fort, which also became known as the Hansen Home, the coastal fortification sitting at the opposite end of the anchorage from Fig Tree Fort.